Saudi Arabia is consuming its most valuable global asset—oil—to secure its most basic human necessity: water.

In June 2024, the Kingdom consumed 1.419 million barrels of oil per day to keep its electricity grid online—the highest level in two years[10]. But the surprising driver of that spike wasn’t industrial output or summer air conditioning: it was desalination.

Desalination already accounts for more than 6% of Saudi Arabia’s total electricity consumption—roughly 17 TWh in 2020—and demand is accelerating with population growth, expanding tourism, and giga-projects like NEOM[7][4][5]. As this analysis shows, the Kingdom’s growing reliance on fossil-powered desalination poses a structural threat to the very energy transition it is attempting to lead.

The strategic dilemma is simple: water security is non-negotiable. But if desalination continues to rely on oil and gas, every new plant quietly sabotages Saudi Arabia’s emissions targets, domestic energy efficiency, and global export position.

Why Solar Desalination Should Be the Norm—Not the Niche

Saudi NEOM's world-first “solar dome” desalination pilot.

Saudi Arabia has every technical advantage needed to solve this problem. With more than 2,200 kWh/m² of annual solar irradiance and a solar market expanding at 51% CAGR through 2029[3][8], the case for renewable desalination is overwhelming.

Projects like Al Khafji—the world’s largest solar-powered desalination plant—already supply drinking water for 255,000 people per day and remove the need for 16,000 barrels of crude oil consumption daily[1][12].

Yet despite this success, renewable desalination remains siloed. Without binding mandates or cross-agency integration, Saudi Arabia continues to treat solar-powered desalination as a demonstration rather than a default. It is supported rhetorically, but not institutionalized in policy[11].

What My Model Shows

LEAP energy model (target scenario): Solar becomes the Kingdom’s most cost-effective generation source.

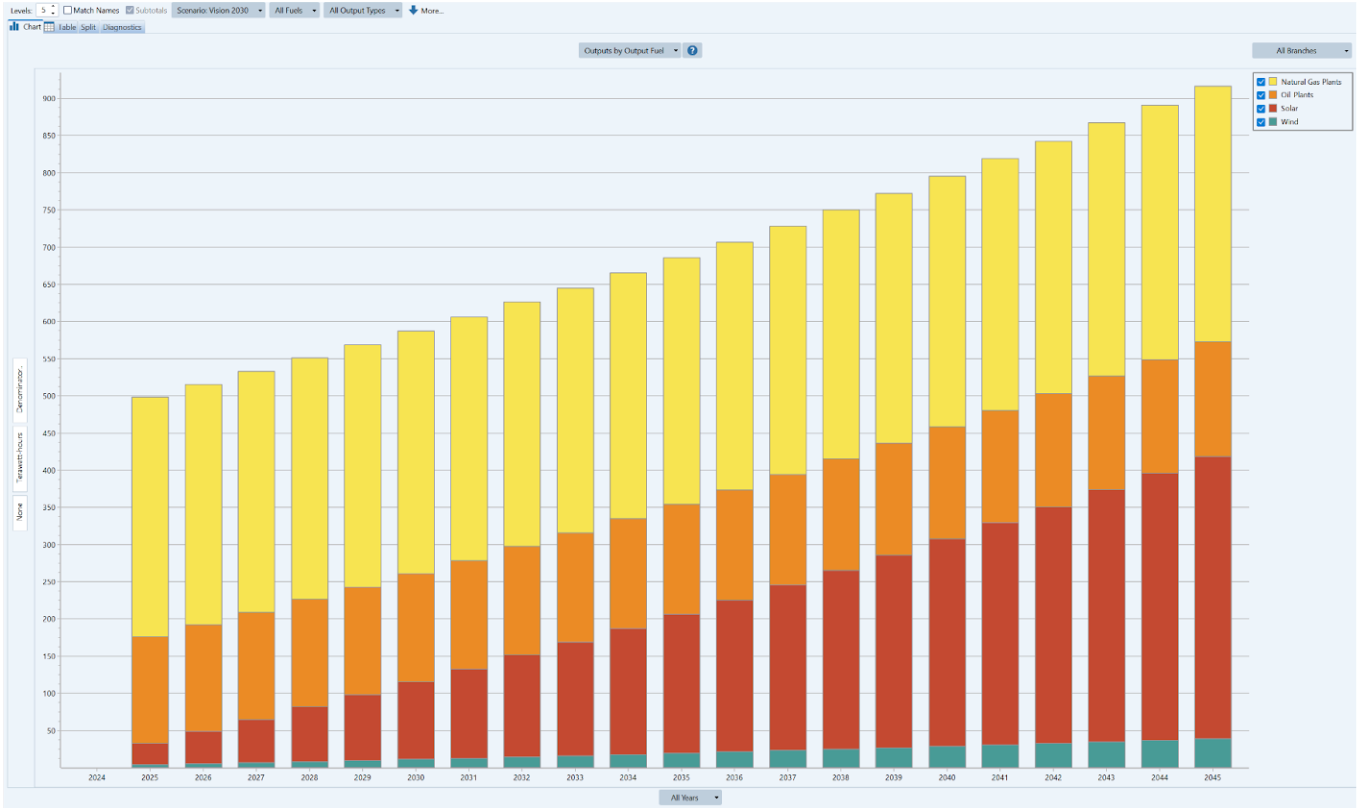

Using a LEAP-based energy model, I simulated a policy-driven transition through 2045 focused on desalination’s electricity demand. The graph above highlights the evolution of energy sources under a 50% renewable target.

In the early years, oil (yellow) and natural gas (orange) dominate. But when renewable procurement rules are introduced and capital spending accelerates, solar (red) expands aggressively—eventually becoming the largest non-fossil contributor to the electricity mix.

Based on Saudi Arabia’s 2024 solar auction, PV power now costs as little as $0.0129 per kWh[2]—the lowest price ever recorded globally. At this rate, solar is cheaper, more predictable, and more scalable than fossil alternatives.

When projected water demand is layered into this model—rising from 17 TWh in 2020 to nearly 40 TWh by 2045—the implications become stark. Without policy intervention, fossil fuels will supply nearly all of that increase.

But under a renewable mandate requiring desalination plants to source at least 50% of electricity from renewables, solar alone could supply up to 20 TWh of clean, desalinated water by 2045.

This creates strategic flexibility: reduced domestic oil consumption increases Saudi Arabia’s ability to export crude, buffer market volatility, and reinforce its global leadership in climate diplomacy at a time when credibility increasingly depends on measurable action.

Four Policy Tools That Actually Move the Needle

1. Mandate renewable integration. Require all new desalination facilities to source at least 50% of electricity from renewables by 2045. This provides regulatory certainty and accelerates clean-tech investment.

2. Designate solar-desalination zones. Establish high-irradiance corridors along the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf as renewable desalination clusters, creating hubs for innovation, jobs, and exportable technology.

3. Reform procurement scoring. Public tenders should award points for low-emissions desalination systems—including renewable integration, life-cycle emissions reduction, and distribution optimization.

4. Fix pricing signals. Saudi consumers currently pay less than 5% of actual production cost[9]. A phased pricing realignment—particularly for inland supply—would reduce system strain and encourage conservation.

These are not radical reforms. Countries like Israel and the UAE have implemented similar procurement standards and coastal solar-desalination clusters with measurable success. Applying them at Saudi scale would be transformational.

The Stakes Are Higher Than They Look

Desalination is no longer a marginal sector. As climate extremes intensify, desalination is becoming central to national water strategies from North Africa to Southern Europe. Its role in food security, population stability, and long-term livability is growing annually.

That makes Saudi Arabia a global bellwether. If the world’s leading oil exporter cannot decarbonize its most essential public utility, what signal does that send to countries attempting similar transitions?

Failing to clean up desalination risks undermining the narrative at the heart of Vision 2030: that economic diversification and sustainability are mutually reinforcing.

But the inverse is powerful. If Saudi Arabia scales renewable desalination—expanding on Al Khafji, restructuring water economics, and aligning policy with technology—it can turn one of its greatest vulnerabilities into an enduring strategic advantage.

Sources Referenced

- AlKhafji Desalination Plant (Vision 2030)

- pv magazine – Saudi Arabia solar tender record

- BX Energy Systems – Solar & Battery Overview

- AGSIW – Saudi Arabia’s Water Future

- Arab Center DC – Costs and Benefits of Gulf Desalination

- Ifri – Desalination & Energy

- PwC – Solar Revolution

- Ouda – Water Tariff Analysis

- EIA Country Brief – Saudi Arabia

- International Trade Administration – Water Sector Overview

- EDI Weekly – Al Khafji Solar Plant